How to differentiate between horror and non-horror films

A quantitative framework to help creators trigger a fear response in their audience.

What are the specific qualities that define a horror film?

Have you ever argued about whether the film Aliens is a horror movie? I have. I don’t think there’s a definitive answer, but I’m curious what you all think.

What differentiates a thriller from a horror? It’s a question with no simple answer. Both can involve death, the supernatural and both scares and jump scares!

Some have pointed out that horror speaks not only to death, but damnation. I can see that - in some cases. But if that’s the dividing line, does that mean Jaws isn’t a horror film?

Horror is certainly subjective, but are there specific commonalities that help define and differentiate it from other genres? As a horror writer, I’d sure like to know, so I went looking for answers in the research literature.

A recent paper by Dubourg and Scrivner attempted to quantify this by focusing on what they believe to be a critical element of the genre: protagonist vulnerability. The paper, “Vulnerability and the computational logic of fear: insights from the horror genre” can be found here.

The authors suggest that the fear induced by horror stories comes from base fears about avoidance of threats and predation, and suggest that two story signals are crucial in understanding these fears: the antagonist threat level and the protagonists’ ability to evade the threat.

They aim to test two hypotheses about horror movies.

Horror narratives are more likely than non-horror narratives to feature vulnerable protagonists who possess low relative formidability compared to their antagonists.

Films with more vulnerable protagonists (greater formidability imbalances between the protagonist and antagonist, favouring the antagonist) will be more frightening.

To test the hypotheses, they identified four key variables to support their analysis. For both the Protagonist (P) and Antagonist (A) formidabilities, they defined the variables to be functions of offensive and defensive capacities, and also the level of persistence.

They also assessed the presence and prominence of threats in movies. Films with a highly formidable antagonist may not be scary if the threat is rarely encountered, whereas a constant, looming threat can amplify fear even if the antagonist is not overwhelmingly powerful. They therefore defined a Threat Presence (T) variable to measure the extent to which the antagonist or their influence is felt throughout the story.

Another constructed variable they identified was the danger level posed by the environment (or context), as some inherently decrease the likelihood of survival. The Environmental Hostility (E) is therefore a measure of how dangerous the setting is.

They further postulated the existence of a composite scalar variable: the Protagonist Vulnerability Index (PVI) which they defined as PVI = (A/P)*E*T, which is dependent on the relative formidability of the protagonist to the antagonist. They further state that this was empirically derived using the data, and that other formulas show similar behaviours.

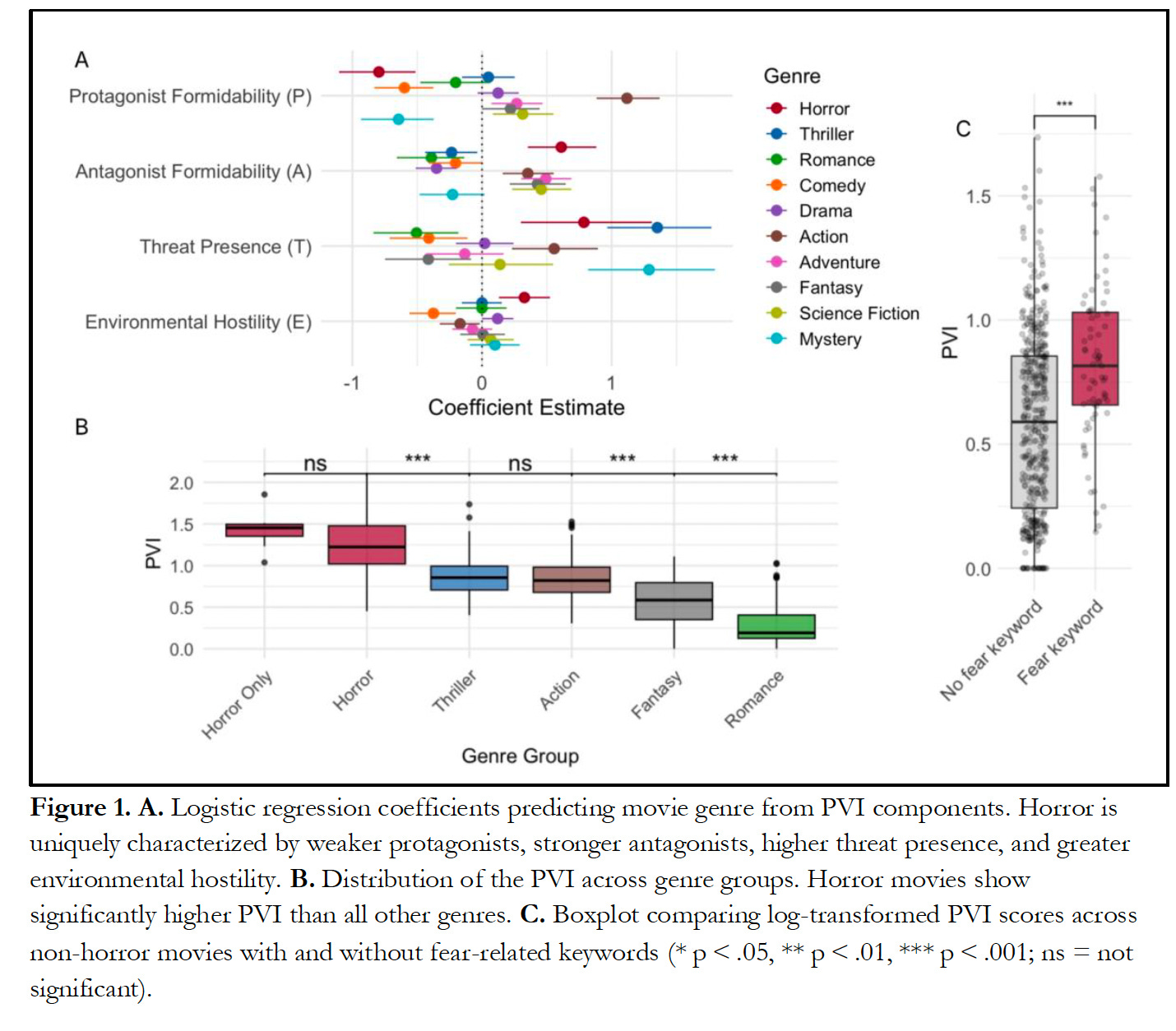

691 movies were identified as scored using the PVI variable, which they hoped would help differentiate horror movies from other genres of film: films classified as horror in combination with other genres, thriller, action, fantasy, and romance. Pair-wise analysis found that horror films had statistically significant higher PVI values than all other categories (p < .001), with the sole exception of the comparison between horror and hybrid-horror, which was not significantly different.

They re-tested the data using a simplified PVI value dependent only on the A/P ratio, and found the same results. Thus, knowing how dominant/vulnerable the protagonist is, relative to the antagonist, is sufficient predictive of whether a film is horror or not - as shown in the figure below:

To test the second hypothesis, the authors examined IMDB keywords for each of the films in the dataset, specifically to identify those which were not classified as horror, but did have a keyword tagged with “fear.” Thus, the films can be divided into those tagged with “fear” and those that are not. Simple analysis showed a statistically significant difference between these two groups, also indicated in the boxplot above.

This suggests PVI is a way to not only differentiate genre, but also tracks the presence of fear-evoking content.

Finally, they also embarked on an audience study using Facebook users movie data to determine the relationship between audience factors and PVI. The details of the analysis are not important, but the study found preferences for films with high-PVI varied: people who were high in openness, but low in agreeableness, conscientiousness, and extraversion were more likely to enjoy such films. There was also a significant interaction between neuroticism and openness indicating that curiosity can modulate avoidance, enabling anxious people to engage with threatening content

The study suggests that horror films are distinct because they feature weaker protagonists, stronger antagonists, more persistent threats, and more hostile environments than other genres. Their analysis also suggests PVI values are potential predictors of fear responses in viewers.

They further speculate that the PVI value tracks relative danger, and when it exceeds a certain point, it triggers primal fear responses in the audience, although this was not tested in the paper.

What does it mean for creators?

As a trained physicist, I love it when we can model complex phenomena using simple variables. But, I’m also aware that often (most of the time) such reductive analysis misses the nuance, and the fascinating parts, of a given problem.

With the above caveat in mind, my takeaway is that these four variables are interesting elements to consider when crafting a horror narrative. By tweaking elements of a story to maximise PVI values, this can potentially stimulate a critical fear response in the audience and therefore make the narrative more scary.

So does this suffice to help us differentiate between horror and non-horror films? I suspect not. As the audience data shows, PVI can impact different personality-types in different ways, and thus perception of what constitutes horror (or not) is still a function of the individual.

But the framework presented here does offer interesting structures for creators to play with as they design their stories. Finding the right balance between the A, P, T, and E variables can go a long way to trigger a fear response, and that could be the difference between a satisfying horror story, and a less-satisfying thriller. Whether this framework is applicable beyond movies to support creators in other formats, is also an interesting question.

Speaking of horror…

I’m almost finished curating and editing an incredible horror and dark fiction anthology about victuals! This is a 380-page book featuring 28 stories from a host of exciting authors, and is coming to Kickstarter very soon!

Please check out the pre-launch page, sign up for notifications, and help spread the word to your friends (and enemies)!

If you enjoyed this deep dive, why not check out some older posts!

The three types of horror fan

Most of us know adrenaline junkies; that friend who always has to turn everything up to eleven - even when they don’t need to.

Cheers

John

I have never thought about how most horror movies feature more vulnerable or weaker protagonists and stronger antagonists but that's a great point. That is how most horror movies go. And I am thinking most people consider Jaws horror, but it's always been hard for me to do that. I really think of it as a thriller. Thrillers usually involve strong antagonists and strong protagonists, which Jaws has. The three men fighting the shark are all strong in their own ways. And I've never thought it had that horror movie "feel". Jaws is a monster but he's also a very real monster. It's a shark. I mean, the guys in The Edge were running from a monster but it's a bear. That doesn't feel like horror to me. Excellent breakdown, John. Thank you for sharing.

If Alien isn't a horror film then neither is The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, or The Hills Have Eyes.

Alien is a monster movie...that makes it a horror film. It's that simple.