Dialling up the fear

Lessons from research on how to make horror stories even scarier!

Hi folks,

As we head towards ‘Ween season, my thoughts inevitably turn to horror movies - and not because I have a new horror anthology ready to launch on Kickstarter!

I had a lot of great reaction and interaction with the last post, which discussed recent attempts to quantify the constituent elements of a horror movie.

The poll, in the post, asked readers whether Aliens (not Alien) was a horror movie, or whether it was something else. The results were 80% in favour and 20% arguing it was something else. This poll was presented before the content of the post, but I suspect many people would not have changed their minds about their vote if they had been polled again.

So, is Aliens a horror movie or not?

I don’t know. The real question is whether it’s an enjoyable movie that I would watch again. Spoiler alert: the answer is yes.

While I was intrigued by the proposal put forward in the previous post, I was also skeptical that it was enough to capture all the context that we expose ourselves to when watching horror films for entertainment. Sure, I think there are many lessons there for creators to consider when developing the antagonist and protagonist of the story, but I feel there’s more to it than that.

What about monster movies? What about monster-adjacent movies likes Jaws or Rogue, where the ‘monster’ is just a hungry, pissed-off animal? How would these rate on the PVI scale?

Are they even horror movies?

I think that’s the big question that settled in my head as I read that Dubourg and Scrivener paper. Is Jaws scary AF? You bet. But is it just a terrifying thriller? Or does it cross the boundary into horror?

I’m one of those people who believes you can have scary movies that are not horror films, which means there are no easy answers. At least for me.

But it got me thinking about the nature of fear, the role it plays in films, and how creators can better manipulate it when telling their stories. After some searches, I finally landed on an interesting paper by Lauri Nummenmaa on the psychology and neurobiology of horror movies1, which has some useful insights on what happens inside the brain when exposed to horror films, and how fear can be dialled-up and down, as needed.

What happens in the brain

On the neurobiology side, research shows that there are two dominant functions that determine our fear response. There is the mid-brain circuit, which is responsible for “fight-or-flight” mode, but also the frontal cortex (specifically governed by the amygdala), which is where our avoidance strategies are developed when a threat is present, but not yet imminent. Our fear response is actually generated by the dynamic interplay between these two functions.

In fact, the amygdala responds quickly to any perceived threat; much more quickly than the contextual parts of the brain, which would assure us we are safe (when watching horror films) Therefore, we are sensitive to signs of impending danger, which is why we feel unsettled long before any moment of terror in a horror movie.

The fear system operates at different rates, first perceived rapidly through the frontal cortex and regulated by the contextual brain, but as the threat becomes closer, the circuit shifts to become driven by mid-brain function. This suggests that one way to induce prolonged fear in the audience is to slow the activation of the contextual parts of the brain by immersing the audience in the narrative. This keeps the amygdala in charge, thus inducing prolonged fear, which primes the viewer for a subsequent jump-scare.

How to harness neurobiology to induce fear

The interplay between brain function needs careful balance, much like the pacing of a story. Dread can be built slowly, and can culminate in a jump-scare or shock for maximum power.

But balance is needed. Too many jump-scares in a short space of time actually drains them of their power, as the brain becomes indifferent to what it has to process.

Further, if the narrative becomes too repetitive i.e., predictable for the audience, it also becomes less scary. Unpredictability is therefore a key tool for storytellers who are looking to maximize the fear factor.

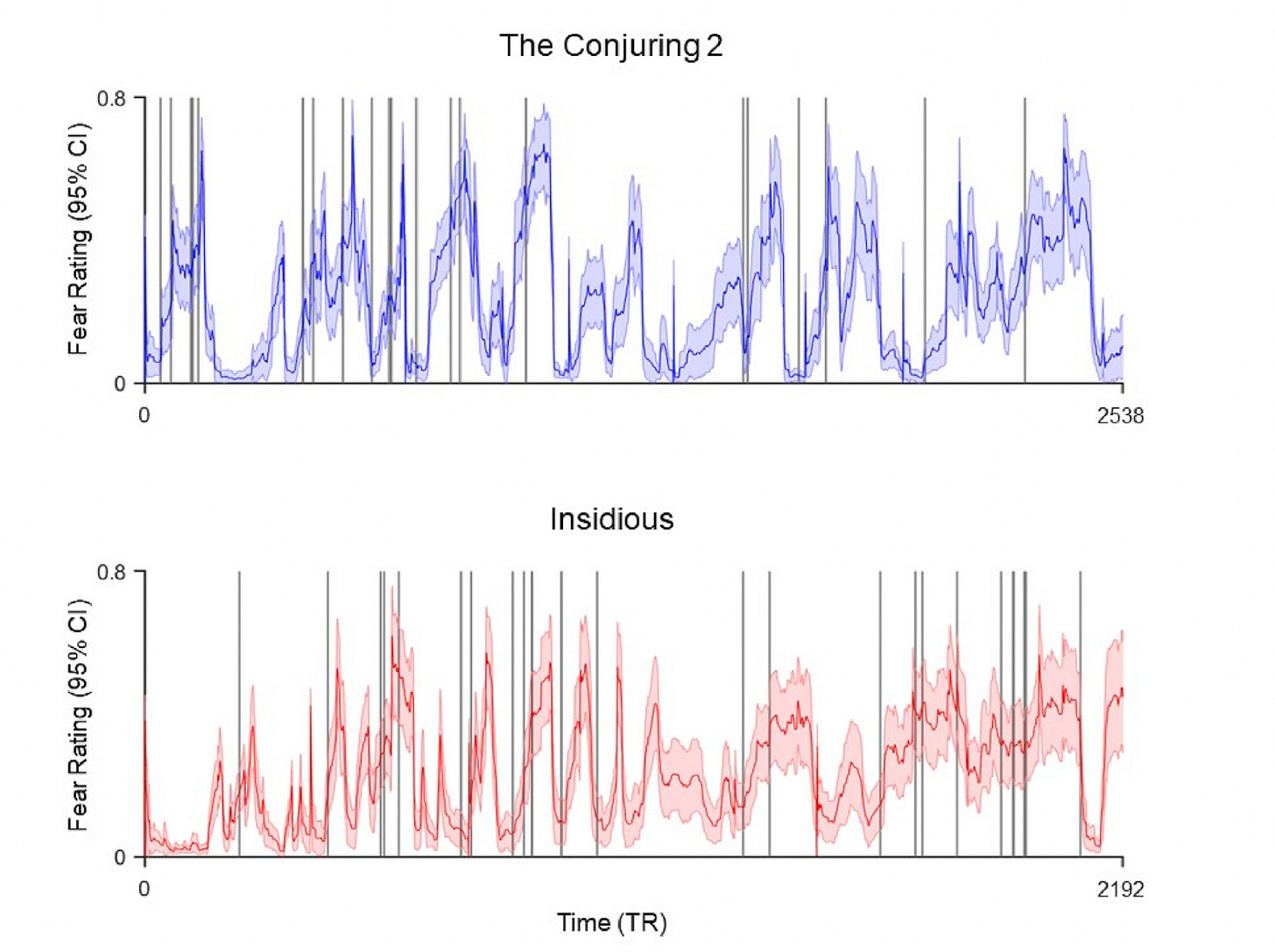

This is demonstrated more clearly from the experiment reported on by Hudson et al2, where audience members were asked to watch one of two recent horror films, and given a slider to record their fear level in real-time during the screening. The mean dynamic fear ratings are shown in the image below, where the black vertical lines are identifiable jump-scares.

The peaks and troughs here tell the important story. Variation and unpredictably are key for stoking fear.

The fear rating peaks are strongly associated with the presence of jump-scares, as you can imagine. But what was also interesting was the experiment also measured Inter-Subject Correlation or ISC (essentially a measure of how similar the neural activity was in each audience member), and found strong (Pearson) correlation between ISC and fear rating (r=0.756 for Conjuring, and r=0.630 for Insidious). This tells us that this is an audience-level effect, i.e., the movie induces similar neural activity in the brains of different people.

How horror taps into core fears

The paper then focuses on a (very) brief overview of induced fears, which culminates n the following recommendation: vicarious fear can be more easily evoked when we have strong empathy with the protagonist. While the paper goes on to discuss issues of likeability (which, as a writer, always makes me cringe) and youth, I think the general point here is aligned with the first recommendation. Strong empathy with the protagonist helps immerse the audience in the context of the story.

The paper goes on to identify core fears, including:

Fear of the unknown, which the article argues could be a fundamental fear, as it explains many other fears. There are many ways to lean into this fear for storytelling, but it’s again important to focus on balance. While unpredictability is a good thing, people need to feel that there are rules to the game for us to enjoy the fear experience.

Fear of loneliness is important for humans, because lack of social connections is associated with premature death. It makes us anxious and vulnerable, which can be used to great effect in horror stories.

Fear of strangers is also argued as a fundamental fear, in that we are always scared of the ‘other’ such as monsters, but are more terrified when the ‘other’ has a form more closely resembling a person, e.g., zombies. i.e., entities that reside in the ‘uncanny valley.’ Thus, antagonists who are carefully situated in the uncanny valley can be more terrifying characters, provided they are not too human-like in behaviour.

Fear of the dark, is something we may grapple with as children. The darkness blinds us and makes us anxious, because it creates uncertainty. Our brains are hard-wired to detect visual signals, so when there are none, this can create anxiety and the desire for the brain to complete any missing information it receives. It is argued that this is why we see faces in mirrors when we stare at them in a dimly-lit room (a real phenomenon).

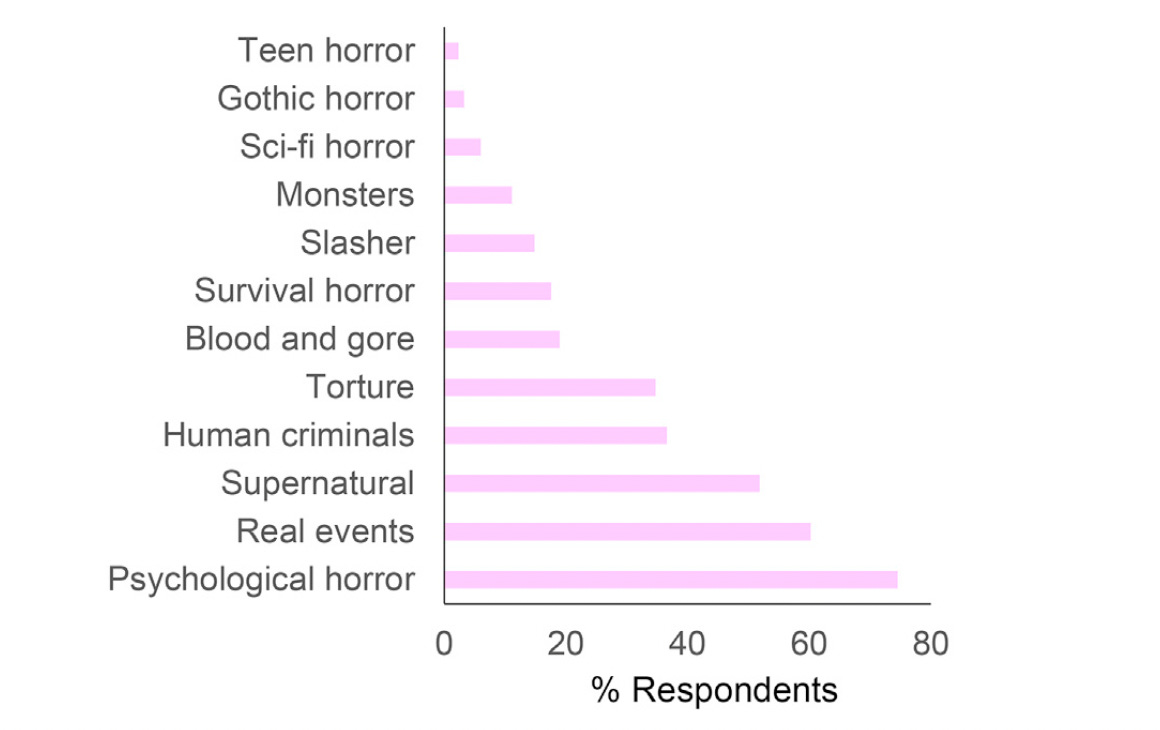

There are many sub-genres of horror movie, and each comes preloaded with tropes, expectations, and other information that the audience already understands at some level (even if only subconsciously). If a sub-genre is perceived to be scary, then it can be easier for creators to generate fear, whereas if the sub-genre is not assumed to be scary, it can be harder for creators to generate fear without breaking the expectations of audiences. So, a key point is that creators need to know which sub-genres are perceived to be the most scary. The Hudson et al. paper explored this within the cohort under study, and found the following findings on what was reported to be the scariest sub-genre.

These responses suggest that the scariest horror films were those most closely connected to our perception of reality (i.e., plausible settings). This finding is similar to the one I discussed in an old paper (article linked below) which found that Psychological horror (69%) was the most favoured horror movie sub-genre amongst dedicated horror fans.

One could argue that slasher or even torture movies are set in the “real world,” however, I think what this list speaks to is plausibility; a rapid assessment made by the audience member about whether this is within their mental scope, or something beyond.

This is why Jaws is a truly terrifying movie, but not necessarily a horror movie (IMHO - I’m sure you may have a different opinion) and why hybrid-horror like sci-fi horror, is harder for many people to buy-into because they first have to get over the sci-fi elements of the story before they even get into the horror aspect. That’s not to say these films can’t be done well, but it may require more cognitive effort on the part of the audience, which reduces the fear level.

This may only be true for movies, and perhaps comics. For books, the reader already has to co-create the world with the author, which may make sci-fi horror much scarier (and certainly much cheaper to render) than in film.

The lesson for creators is that horror stories in plausible settings appear - at least in visually-driven stories - to be scarier than ones that seem less plausible. Leaning into this convention can, again, help increase the overall fear threshold.

What does it mean for creators?

There are several takeaways here for creators, however, the publications here are focused on movies, and so the implications for creators in other formats (e.g., books, podcasts) may be wildly different. There may be some overlap for comic and game creators, which are both visual-first formats, but comics also lack the audio information that games and movies both possess (which helps with immersion), so it may still need to be examined from a different perspective.

Prolonged fear can be induced by fully immersing the audience in the narrative. This is likely easiest to do in film, but I think the general point holds across formats, particularly if the protagonist generates strong feelings of empathy. I suspect this is also why horror stories in plausible settings are deemed more scary, because they contribute more easily to the immersion. The audience member can more easily put themselves into the material, living vicariously through the actions of the protagonist, while still recognizing that there are protective barriers to keep them safe (i.e., they’re watching a movie in a room with other people).

While I think empathetic protagonists can be created in any story and format, the immersion may be harder to accomplish in comics and books; not impossible, but certainly more challenging.

Similarly, stories need to have contrasting moments e.g., humour to break the tension after a massive scare. This variation appears to prime the audience for more prolonged and powerful fear, but also needs to keep them off balance; predictable beats become less scary once recognized. I think this one is perhaps the most useful consideration for creators. I believe stories need to have a sense of inevitability, but that doesn’t mean they are predictable - and thinking up ways to constantly make a left-turn that the audience wasn’t expecting, is a good way to create uncertainty - and then if this is aligned with elements that generate a fear response, it can lead to memorable terrors.

What other lessons do you see here for creators? Let me know in the comments!

Lauri Nummenmaa. Psychology and neurobiology of horror movies. 2021, March 4. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/b8tgs

Matthew Hudson, Kerttu Seppälä, Vesa Putkinen, Lihua Sun, Enrico Glerean, Tomi Karjalainen, Henry K. Karlsson, Jussi Hirvonen, Lauri Nummenmaa. Dissociable neural systems for unconditioned acute and sustained fear, NeuroImage, Volume 216, 2020, 116522, ISSN 1053-8119, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2020.116522.